In 1967, Geraldine Norman was tasked with leading an editorial collaboration between the London Times and Sotheby’s. The project galvanized the conceptualization of art as an investment asset.

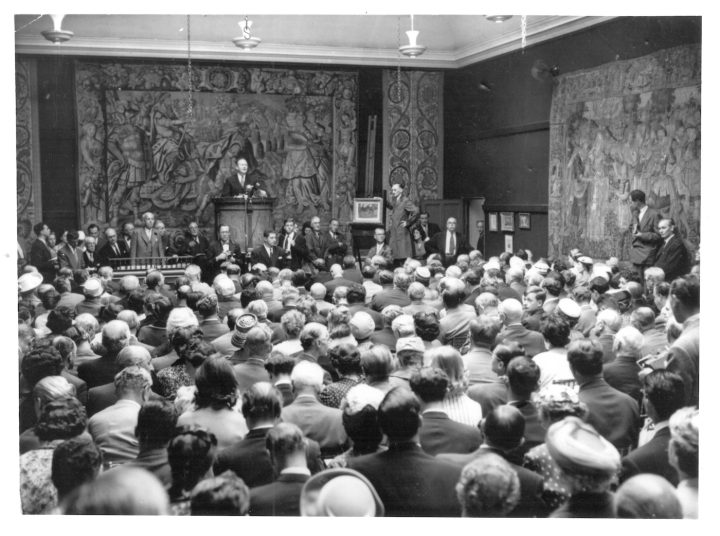

Peter Wilson presiding over the Goldschmidt sale at Sotheby’s, October 15, 1958. For maximum drama, Wilson limited the sale to seven star lots. Guests included Kirk Douglas, Somerset Maugham, and Lady Churchill. The rising prices paid for Impressionist paintings during the 1950s caught the attention of the press and attracted a surge of new buyers (image courtesy Sotheby’s)

“Works of art have proved to be the best investment, better than the majority of stocks and shares in the last thirty years.”

This was the confident declaration of Peter Wilson, the then chairman of Sotheby’s, during his 1966 appearance on the BBC’s Money Programme. Though he was only eight years into his chairmanship, Wilson had already overhauled the fusty image of the art trade. His ingenious pre-sale marketing efforts, celebrity invitations, and black-tie sales had transformed Sotheby’s auctions into major news affairs, and deepened the perception of Christie’s as an antiquated rival.

Reacting shrewdly to the post-war wave of prosperity, Wilson was determined to bring newly moneyed buyers into the fold. He sought to convince businessmen and bankers that collecting was no longer the exclusive preserve of cultured, old-money dynasties such as the Rothschilds, Rockefellers, or Mellons. Crucially, Wilson wanted to instill the notion that art can be an investment. The sudden and precipitous rise of the Impressionist art market during the 1950s may be cited as proof of this. If you inherited an Impressionist painting, you could now sell it for vastly more than your family paid to acquire it. Wilson’s idea just needed to be packaged in an immediate and compelling fashion.

Get the latest art news, reviews and opinions from Hyperallergic.Sign up

A year after Wilson’s television appearance, twenty-seven-year-old Geraldine Keen — now Geraldine Norman — received a letter in Rome. A graduate of Oxford University and UCLA, Norman had left her job as an editorial statistician for the Times newspaper in London to work for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. The letter was a job offer from the paper’s City editor, George Pulay, asking Norman whether she would consider returning to London. He wanted her to spearhead a new editorial collaboration between the Times and Sotheby’s.

* * *

Few people active in the art world today have heard of the Times-Sotheby Index. Those who have are most likely veteran art dealers or retired auction staff. Web results primarily consist of library entries for Norman’s 1971 book on the project.

The first Times-Sotheby Index, published November 25, 1967 (used with the kind permission of The Times Archive) (click to enlarge)

Published regularly in the Times between 1967–1971, the Times-Sotheby Index purported to chart the changing prices of art sold at auction. Each feature centered on a single movement or department (Impressionism, English silver, Chinese ceramics, etc.) and were accompanied by charts that illustrated sales prices from the early 1950s to the present.

The first index, published on November 25, 1967, includes seven prominent graphs dedicated to Impressionism. Six charted the prices paid for specific artists since 1950–52: Renoir (“up 405%”), Fantin-Latour (“up 780%”), Monet (“up 1,100%”), Sisley (“up 1,150%”), Boudin (“up 835%”), Pissarro (“up 845%”). The seventh graph includes three indices, the value of Impressionist paintings, US share prices, and UK share prices — the former vastly outpacing the latter. The message was clear: Art is a hot commodity, and its sale value can and should be conceived in much the same way as a stock on the Dow Jones or FTSE 100.

The market for contemporary art has grown exponentially since the 1960s. It’s now commonplace to describe the intricacies of an artist’s particular “resale value,” or “collector base.” Innumerable artworks reside out of sight within heavily secured free ports, where their owners avoid custom duties. The press routinely report record sales, rehashing features on the best-selling artists and publishing listicles on the world’s most expensive works. Companies such as Artnet, Collectrium, Artprice, and ArtRank sell their data and insights on sales and trends. Speculation is the norm. However, in 1967, the Times-Sotheby Index’s brazenly analytic conception of art’s value was, with a few exceptions, unprecedented and highly radical.

A graph from the the first Times-Sotheby Index (used with kind permission from The Times Archive)

“Our culture has been schooled to think of works of art as investment commodities,” wrote Robert Hughes in his renowned 1984 essay, “Art & Money.” “The art market we have today did not pop up overnight … I think of it as beginning with a curious enterprise called the Times/Sotheby Art Indexes.” The critic continued:

Perhaps it was the graphs that did it. They gave these tendentious little essays the trustworthy look of the Times financial page. They objectified the hitherto dicey idea of art investment. They made it seem hard-headed and realistic to own art.

The index was reportedly conceived during a lunch between Pulay, Wilson, and Brigadier Stanley Clark. As Sotheby’s PR agent, Clark had played an instrumental role in the company’s 1964 acquisition of Parke-Bernet auction house, which vastly expanded Sotheby’s presence in the US. (Christie’s did not open its own sale room in New York until 1977.)

Together, Clark and Wilson landed a spectacular PR coup in convincing the Times to collaborate on the feature. The name alone guaranteed a tranche of regular free press for Sotheby’s and the association with the Times instantly bestowed authority on the index’s findings. Though they conceived it, neither Wilson nor Clark actually brought the index to life. That responsibility fell squarely on Geraldine Norman’s shoulders.

Geraldine’s biography and portrait on the dust jacket of Money and Art: A Study Based on the Times-Sotheby Index (1971) (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic unless otherwise noted)

I interviewed Norman, now 78, over the phone. By her own admission, the project did not get off to a smooth start. “I was worried because I thought art actually can’t be valued and that it’s ridiculous to put prices on things and measure them in an index,” Norman told me. “I panicked all one night and at the end of it I decided, well … I may as well do it.”

The project presented an obvious methodological conundrum. Unlike gold or oil, art is not a singular commodity. Every piece is unique, and an artist’s oeuvre will always be comprised of works judged to be of a comparatively higher or lower quality. Aesthetic judgements, regardless of trends or received wisdom, are subjective. Condition, provenance, and size are just a few of the factors that have a bearing on how an artwork is appraised.

Tracking the prices of every Impressionist painting sold at auction would be an unmanageable task, so Norman’s solution was to compromise. For the first index, she focused on six “representative” painters. Monet and Renoir stood as the movement’s perceived masters, while Fantin-Latour and Boudin represented lesser “companions.”

Norman then deferred the issue of quality and variance to a Sotheby’s specialist, who divided up each artist’s oeuvre into groups of “roughly equal intrinsic value,” or as Norman jokingly put it, “from masterpiece down to crap.” To do this, Norman would sit with the relevant specialist and review the sale records for each artist documented by the auction house. Having determined her parameters, Norman tracked the prices paid for each artist before combining the results into a single index. “The method adopted in this study,” Norman announced in the Times, “was to scale the actual price paid for each picture either up or down to an equivalent price for an average example of the artist’s work.” The data included pictures sold by Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Parke-Bernet, and “when possible, the Paris sale rooms since 1950.”